Contrasts and multiple testing

Session 4

MATH 80667A: Experimental Design and Statistical Methods

HEC Montréal

Outline

Outline

Contrasts

Outline

Contrasts

Multiple testing

Planned comparisons

- Oftentimes, we are not interested in the global null hypothesis.

- Rather, we formulate planned comparisons at registration time for effects of interest

Planned comparisons

- Oftentimes, we are not interested in the global null hypothesis.

- Rather, we formulate planned comparisons at registration time for effects of interest

What is the scientific question of interest?

Global null vs contrasts

Global test

Global test

Contrasts

Image source: PNGAll.com, CC-BY-NC 4.0

Analogy here is that the global test is a dim light: it shows there are differences, but does not tell us where. Contrasts are more specific.

Linear contrasts

With K groups, null hypothesis of the form

H0:C=c1μ1+⋯+cKμKweighted sum of subpopulation means=a

Linear contrasts

With K groups, null hypothesis of the form

H0:C=c1μ1+⋯+cKμKweighted sum of subpopulation means=a

Linear combination of

weighted group averages

Examples of linear contrasts

Global mean larger than a?

H0:n1nμ1+⋯+nKnμK≤a

Pairwise comparison

H0:μi=μj,i≠j

Characterization of linear contrasts

- Weights c1,…,cK are specified by the user.

- Mean response in each experimental group is estimated as sample average of observations in that group, ˆμ1,…,ˆμK.

- Assuming equal variance, the contrast statistic behaves in large samples like a Student-t distribution with n−K degrees of freedom.

Sum-to-zero constraint

If c1+⋯+cK=0, the contrast encodes

differences between treatments

rather than information about the overall mean.

Arithmetic example

Setup

group 1

(control)

group 2

(control)

group 3

(praise, reprove, ignore)

Arithmetic example

Setup

group 1

(control)

group 2

(control)

group 3

(praise, reprove, ignore)

Hypotheses of interest

- H01:μpraise=μreproved (attention)

- H02:12(μcontrol1+μcontrol2)=μpraised (encouragement)

This is post-hoc, but supposed we had particular interest in the following hypothesis (for illustration purposes)

Contrasts

With placeholders for each group, write H01:μpraised=μreproved as

0⋅μcontrol1 + 0⋅μcontrol2 + 1⋅μpraised - 1⋅μreproved + 0⋅μignored

The sum of the coefficient vector, c=(0,0,1,−1,0), is zero.

Contrasts

With placeholders for each group, write H01:μpraised=μreproved as

0⋅μcontrol1 + 0⋅μcontrol2 + 1⋅μpraised - 1⋅μreproved + 0⋅μignored

The sum of the coefficient vector, c=(0,0,1,−1,0), is zero.

Similarly, for H02:12(μcontrol1+μcontrol2)=μpraise

12⋅μcontrol1+12⋅μcontrol2−1⋅μpraised+0⋅μreproved+0⋅μignored

The contrast vector is c=(12,12,−1,0,0); entries again sum to zero.

Equivalent formulation is obtained by picking c=(1,1,−2,0,0)

Contrasts in R with emmeans

library(emmeans)linmod <- lm(score ~ group, data = arithmetic)linmod_emm <- emmeans(linmod, specs = 'group')contrast_specif <- list( controlvspraised = c(0.5, 0.5, -1, 0, 0), praisedvsreproved = c(0, 0, 1, -1, 0))contrasts_res <- contrast(object = linmod_emm, method = contrast_specif)# Obtain confidence intervals instead of p-valuesconfint(contrasts_res)Output

| contrast | null.value | estimate | std.error | df | statistic | p.value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| control vs praised | 0 | -8.44 | 1.40 | 40 | -6.01 | <1e-04 |

| praised vs reprove | 0 | 4.00 | 1.62 | 40 | 2.47 | 0.018 |

Confidence intervals

| contrast | lower | upper |

|---|---|---|

| control vs praised | -11.28 | -5.61 |

| praised vs reprove | 0.72 | 7.28 |

One-sided tests

Suppose we postulate that the contrast statistic is bigger than some value a.

- The alternative is Ha:C>a (what we are trying to prove)!

- The null hypothesis is therefore H0:C≤a (Devil's advocate)

It suffices to consider the endpoint C=a (why?)

- If we reject C=a in favour of C>a, all other values of the null hypothesis are even less compatible with the data.

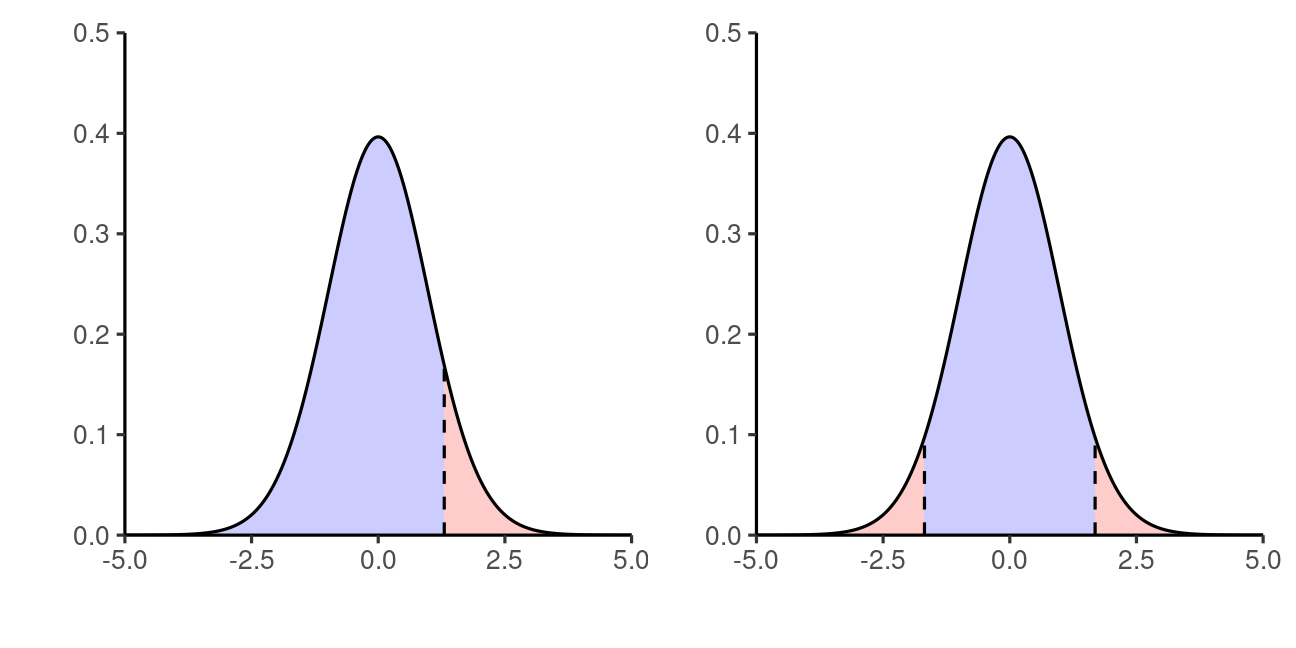

Comparing rejection regions

Rejection regions for a one-sided test (left) and a two-sided test (right).

When to use one-sided tests?

In principle, one-sided tests are more powerful (larger rejection region on one sided).

- However, important to pre-register hypothesis

- can't look at the data before formulating the hypothesis (as always)!

- More logical for follow-up studies and replications.

If you postulate Ha:C>a and the data show the opposite with ˆC≤a, then the p-value for the one-sided test is 1!

Multiple testing

Post-hoc tests

Suppose you decide to look at all pairwise differences

Comparing all pairwise differences: m=(K2) tests

- m=3 tests if K=3 groups,

- m=10 tests if K=5 groups,

- m=45 tests if K=10 groups...

The recommendation for ANOVA is to limit the number of tests to the number of subgroups

There is a catch...

Read the small prints:

If you do a single hypothesis test and

your testing procedure is well calibrated

(meaning the model assumptions are met),

there is a probability α

of making a type I error

if the null hypothesis is true.

How many tests?

Dr. Yoav Benjamini looked at the number of tests performed in the Psychology replication project

The number of tests performed ranged from 4 to 700, with an average of 72.

How many tests?

Dr. Yoav Benjamini looked at the number of tests performed in the Psychology replication project

The number of tests performed ranged from 4 to 700, with an average of 72.

Most studies did not account for selection.

Yoav B. reported that 11/100 engaged with selection, but only cursorily

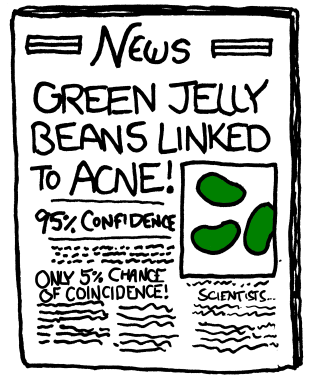

Scientifist, investigate!

- Consider the Cartoon Significant by Randall Munroe (https://xkcd.com/882/)

It highlights two problems: lack of accounting for multiple testing and selective reporting.

Bring students to realize the multiple testing problem: quiz them on potential consequences

Gone fishing

- Having found no difference between group, you decide to stratify with another categorical variable and perform the comparisons for each level (subgroup analysis)

The more tests you perform, the larger the type I error.

Probability of type I error

If we do m independent comparisons, each one at the level α, the probability of making at least one type I error, say α⋆, is

α⋆=1–probability of making no type I error=1−(1−α)m.

With α=0.05

- m=4 tests, α⋆≈0.185.

- m=72 tests, α⋆≈0.975.

Tests need not be independent... but one can show α⋆≤mα.

The first equality holds under the assumption observations (and thus tests) are independent, the second follows from Boole's inequality and does not require independence.

It is an upper bound on the probability of making no type I error

Statistical significance at the 5% level

Why α=5%? Essentially arbitrary...

If one in twenty does not seem high enough odds, we may, if we prefer it, draw the line at one in fifty or one in a hundred. Personally, the writer prefers to set a low standard of significance at the 5 per cent point, and ignore entirely all results which fails to reach this level.

Fisher, R.A. (1926). The arrangement of field experiments. Journal of the Ministry of Agriculture of Great Britain, 33:503-513.

Family of hypothesis

Consider m tests with the corresponding null hypotheses H01,…,H0m.

- The family may depend on the context, but including any hypothesis that is scientifically relevant and could be reported.

Should be chosen a priori and pre-registered

Family of hypothesis

Consider m tests with the corresponding null hypotheses H01,…,H0m.

- The family may depend on the context, but including any hypothesis that is scientifically relevant and could be reported.

Should be chosen a priori and pre-registered

Keep it small: the number of planned comparisons for a one-way ANOVA should be less than the number of groups K.

Researchers do not all agree with this “liberal” approach (i.e., that don't correct for multiplicity even for pre-planned comparisons) and recommend to always control for the familywise or experimentwise Type I error rate. dixit F. Bellavance.

Notation

Define indicators Ri={1if we reject H0i0if we fail to reject H0iVi={1type I error for H0i(Ri=1 and H0i is true)0otherwise

with

- R=R1+⋯+Rm the total number of rejections ( 0≤R≤m ).

- V=V1+⋯+Vm the number of null hypothesis rejected by mistake.

Familywise error rate

Definition: the familywise error rate is the probability of making at least one type I error per family

FWER=Pr(V≥1)

If we use a procedure that controls for the family-wise error rate, we talk about simultaneous inference (or simultaneous coverage for confidence intervals).

Bonferroni's procedure

Consider a family of m hypothesis tests and perform each test at level α/m.

- reject ith null Hi0 if the associated p-value pi≤α/m.

- build confidence intervals similarly with 1−α/m quantiles.

If the (raw) p-values are reported, reject H0i if m×pi≤α (i.e., multiply reported p-values by m)

Often incorrectly applied to a set of significant contrasts, rather than for preplanned comparisons only

Holm's sequential method

Order the p-values of the family of m tests from smallest to largest p(1)≤⋯≤p(m)

associated to null hypothesis H0(1),…,H0(m).

Idea use a different level for each test, more stringent for smaller p-values.

Coupling Holm's method with Bonferroni's procedure: compare p(1) to α(1)=α/m, p(2) to α(2)=α/(m−1), etc.

Holm-Bonferroni procedure is always more powerful than Bonferroni

Sequential Holm-Bonferroni procedure

- order p-values from smallest to largest.

- start with the smallest p-value.

- check significance one test at a time.

- stop when the first non-significant p-value is found or no more test.

Conclusion for Holm-Bonferroni

Reject smallest p-values until you find one that fails, reject rest

If p(j)≥α(j) but p(i)<α(i) for i=1,…,j−1 (all smaller p-values)

- reject H0(1),…,H0(j−1)

- fail to reject H0(j),…,H0(m)

All p-values are lower than their respective cutoff:

If p(i)≤α(i) for all test i=1,…,m

- reject H0(1),…,H0(m)

Numerical example

Consider m=3 tests with raw p-values 0.01, 0.04, 0.02.

| i | p(i) | Bonferroni | Holm-Bonferroni |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.01 | 3×0.01=0.03 | 3×0.01=0.03 |

| 2 | 0.02 | 3×0.02=0.06 | 2×0.02=0.04 |

| 3 | 0.04 | 3×0.04=0.12 | 1×0.04=0.04 |

Reminder of Holm–Bonferroni: multiply by (m−i+1) the ith smallest p-value p(i), compare the product to α.

Why choose Bonferroni's procedure?

- m must be prespecified

- simple and generally applicable (any design)

- but dominated by sequential procedures (Holm-Bonferroni uniformly more powerful)

- low power when the number of test m is large

- also controls for the expected number of false positive, E(V), a more stringent criterion called per-family error rate (PFER)

Careful: adjust for the real number of comparisons made (often reporter just correct only the 'significant tests', which is wrong).

Controlling the average number of errors

The FWER does not make a distinction between one or multiple type I errors.

We can also look at a more stringent criterion

per-family error rate (PFER) i.e., the expected number of false positive

Since FWER=Pr(V≥1)≤E(V)=PFER

any procedure that controls the per-family error rate also controls the familywise error rate. Bonferroni controls both per-family error rate and family-wise error rate.

Confidence intervals for linear contrasts

Given a linear contrast of the form C=c1μ1+⋯+cKμK with c1+⋯cK=0, we build confidence intervals as usual

ˆC±critical value׈se(ˆC)

Different methods provide control for FWER by modifying the critical value.

All methods valid with equal group variances and independent observations.

Assuming we care only about mean differences between experimental conditions

FWER control in ANOVA

- Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD) method: to compare (all) pairwise differences between subgroups, based on the largest possible pairwise mean differences, with extensions for unbalanced samples.

- Scheffé's method: applies to any contrast (properties depends on sample size n and number of groups K, not the number of test). Better than Bonferroni if m is large. Can be used for any design, but not powerful.

- Dunnett's method: only for all pairwise contrasts relative to a specific baseline (control).

Described in Dean, Voss and Draguljić (2017), Section 4.4 in more details.

Tukey's honest significant difference

Control for all pairwise comparisons

Idea: controlling for the range max{μ1,…,μK}−min{μ1,…μK} automatically controls FWER for other pairwise differences.

Critical values based on ''Studentized range'' distribution

Assumptions: equal variance, equal number of observations in each experimental condition.

Scheffé's criterion

Control for all

possible linear contrasts

Critical value is √(K−1)F,

where F is the (1−α) quantile

of the F(K−1,n−K) distribution.

Allows for data snooping

(post-hoc hypothesis)

But not powerful...

Adjustment for one-way ANOVA

Take home message:

- same as usual, only with different critical values

- larger cutoffs for p-values when procedure accounts for more tests

Everything is obtained using software.

Numerical example

With K=5 groups and n=9 individuals per group (arithmetic example), critical value for two-sided test of zero difference with standardized t-test statistic and α=5% are

- Scheffé's (all contrasts): 3.229

- Tukey's (all pairwise differences): 2.856

- Dunnett's (difference to baseline): 2.543

- unadjusted Student's t-distribution: 2.021

These were derived from the output of the function, sometimes by reverse-engineering.

agricolae::scheffe.test

TukeyHSD, agricolae::HSD.test

DescTools::DunnettTest

Sometimes, there are too many tests...

Scaling back expectations...

A simultaneous procedure that controls family-wise error rate (FWER) ensure any selected test has type I error α.

With thousands of tests, this is too stringent a criterion.

Scaling back expectations...

A simultaneous procedure that controls family-wise error rate (FWER) ensure any selected test has type I error α.

With thousands of tests, this is too stringent a criterion.

The false discovery rate (FDR) provides a guarantee for the proportion among selected discoveries (tests for which we reject the null hypothesis).

Why use it? the false discovery rate is scalable:

- 2 type I errors out of 4 tests is unacceptable.

- 2 type I errors out of 100 tests is probably okay.

False discovery rate

Suppose that m0 out of m null hypothesis are true

The false discovery rate is the proportion of false discovery among rejected nulls,

FDR={VRR>0 (if one or more rejection),0R=0 (if no rejection).

False discovery rate offers weak-FWER control the property is only guaranteed under the scenario where all null hypotheses are true.

Controlling false discovery rate

The Benjamini-Hochberg (1995) procedure for controlling false discovery rate is:

- Order the p-values from the m tests from smallest to largest: p(1)≤⋯≤p(m)

- For level α (e.g., α=0.05), set k=max{i:p(i)≤imα}

- Reject H0(1),…,H0(k).

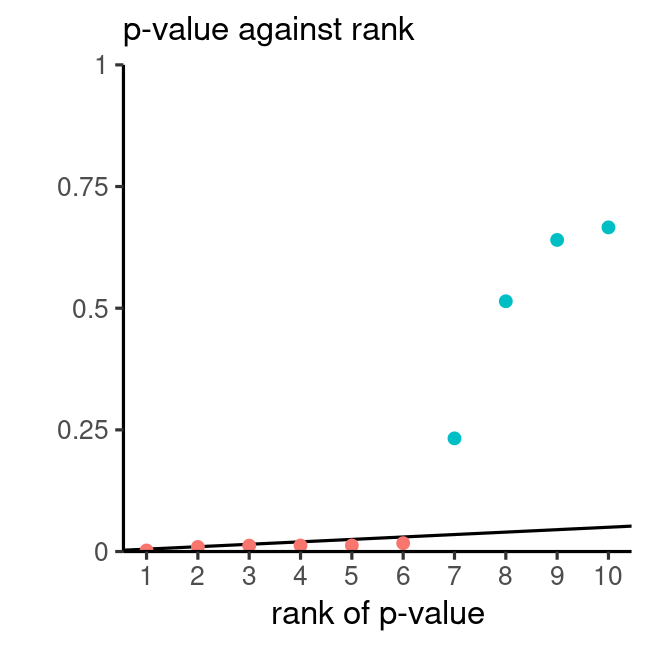

Benjamini-Hochberg in a picture

- Plot p-values (y-axis) against their rank (x-axis)

(the smallest p-value has rank 1, the largest has rank m).

- Draw the line y=α/mx

(zero intercept, slope α/m)

- Reject all null hypotheses associated to p-values located before the first time a point falls above the line.

Recap 1

- The test of equality of variance of the one-way ANOVA is seldom of interest (too general or vague)

- Rather, we care about specific comparisons (often linear contrasts)

- Must specify ahead of time which comparisons are of interest

- otherwise it's easy to find something significant!

- and multiplicity correction will be unfavorable.

Recap 2

- Researchers often carry lots of hypothesis testing tests

- the more you look, the more you find!

- One of the many reasons for the replication crisis!

- Thus want to control probability of making a type I error (condemn innocent, incorrect finding) among all m tests performed

- aka family-wise error rate (FWER)

- Downside of multiplicity correction/adjustment is loss of power

- upside is (more robust findings).

Recap 3

ANOVA specific solutions (assuming equal variance, balanced large samples...)

- Tukey's HSD (all pairwise differences),

- Dunnett's method (only differences relative to a reference category)

- Scheffé's method (all potential linear contrasts)

Outside of ANOVA, some more general recipes:

- FWER: Bonferroni (suboptimal), Bonferroni-Holm (more powerful)

- FDR: Benjamini-Hochberg

Pick the one that controls FWER, but penalizes less!

Example of the last point is comparison between Bonferroni and Scheffé: with large number of tests, the latter may be less stringent and lead to more discovery while having guarantees for the FWER