Introduction to causal inference

Session 11

MATH 80667A: Experimental Design and Statistical Methods

HEC Montréal

Outline

Outline

Basics of causal inference

Outline

Basics of causal inferenceDirected acyclic graphs

Outline

Basics of causal inferenceDirected acyclic graphs Causal mediation

Causal inference

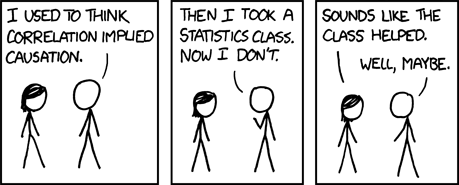

Correlation is not causation

xkcd comic 552 by Randall Munroe, CC BY-NC 2.5 license. Alt text: Correlation doesn't imply causation, but it does waggle its eyebrows suggestively and gesture furtively while mouthing 'look over there'.

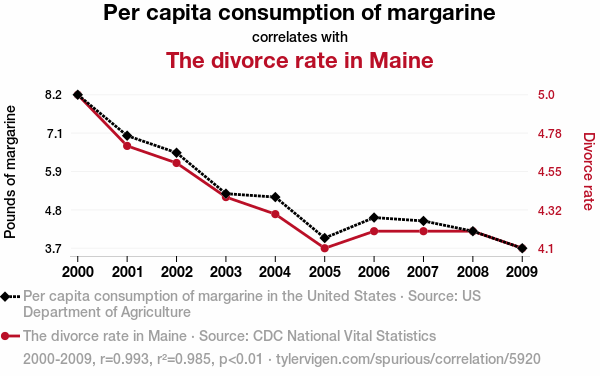

Spurious correlation

Spurious correlation by Tyler Vigen, licensed under CC BY 4.0

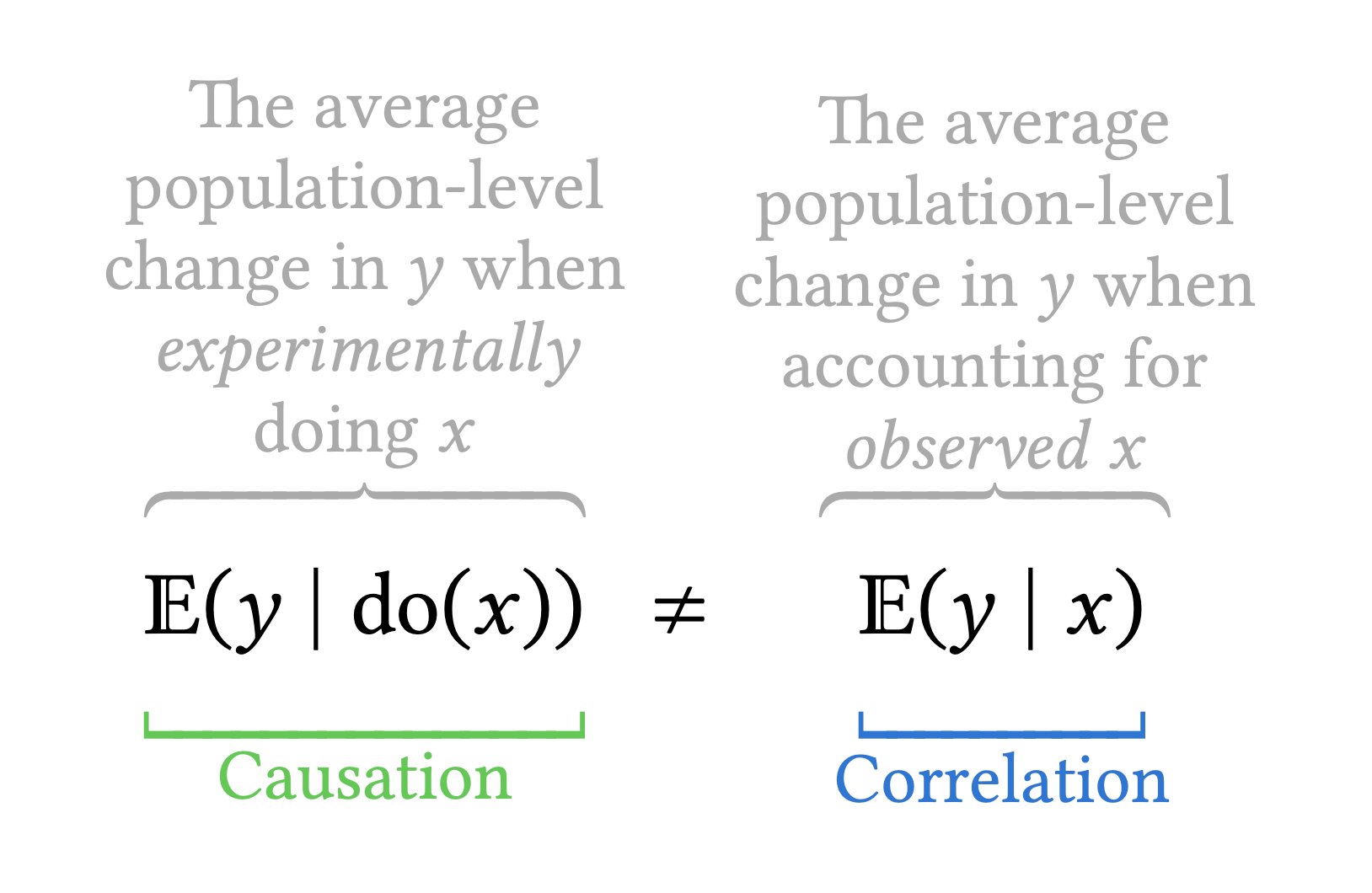

Correlation vs causation

Illustration by Andrew Heiss, licensed under CC BY 4.0

Potential outcomes

For individual i, we postulate the existence of a potential outcomes

- Yi(1) (response for treatment X=1) and

- Yi(0) (response for control X=0).

Both are possible, but only one will be realized.

Observe outcome for a single treatment

- Result Y(X) of your test given that you either party (X=1) or study (X=0) the night before your exam.

Fundamental problem of causal inference

With binary treatment Xi, I observe either Yi∣do(Xi=1) or Yi∣do(Xi=0).

| i | Xi | Yi(0) | Yi(1) | Yi(1)−Yi(0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | ? | 4 | ? |

| 2 | 0 | 3 | ? | ? |

| 3 | 1 | ? | 6 | ? |

| 4 | 0 | 1 | ? | ? |

| 5 | 0 | 5 | ? | ? |

| 6 | 1 | ? | 7 | ? |

Causal assumptions?

Since we can't estimate individual treatment, we consider the average treatment effect (average over population) E{Y(1)−Y(0)}.

The latter can be estimated as

ATE=E(Y∣X=1)expected response amongtreatment group−E(Y∣X=0)expected response amongcontrol group

When is this a valid causal effect?

(Untestable) assumptions

For the ATE to be equivalent to E{Y(1)−Y(0)}, the following are sufficient:

- ignorability, which states that potential outcomes are independent of assignment to treatment

- lack of interference: the outcome of any participant is unaffected by the treatment assignment of other participants.

- consistency: given a treatment X taking level j, the observed value for the response Y∣X=j is equal to the corresponding potential outcome Y(j).

Directed acyclic graphs

Slides by Dr. Andrew Heiss, CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Types of data

Experimental

You have control over which units get treatment

Types of data

Experimental

You have control over which units get treatment

Observational

You don't have control over which units get treatment

Causal diagrams

Directed acyclic graphs (DAGs)

Directed: Each node has an arrow that points to another node

Acyclic: You can't cycle back to a node (and arrows only have one direction)

Graph: A set of nodes (variables) and vertices (arrows indicating interdependence)

Causal diagrams

Directed acyclic graphs (DAGs)

Graphical model of the process that generates the data

Maps your logical model

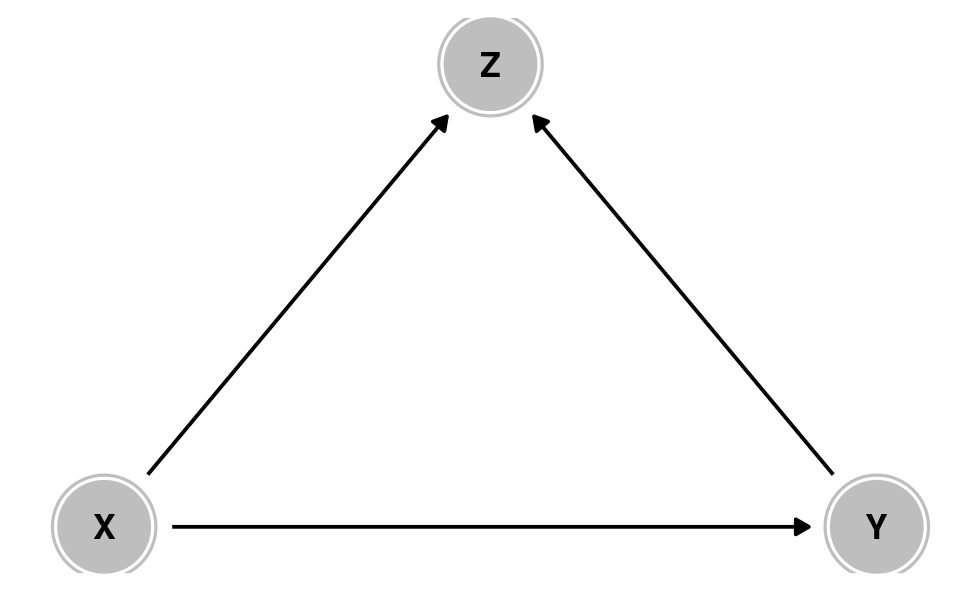

Three types of associations

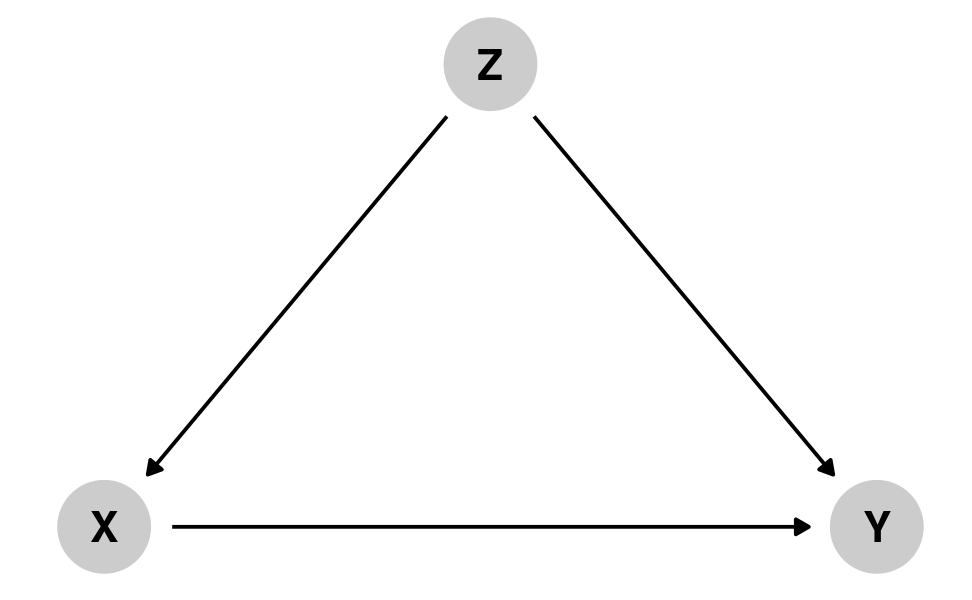

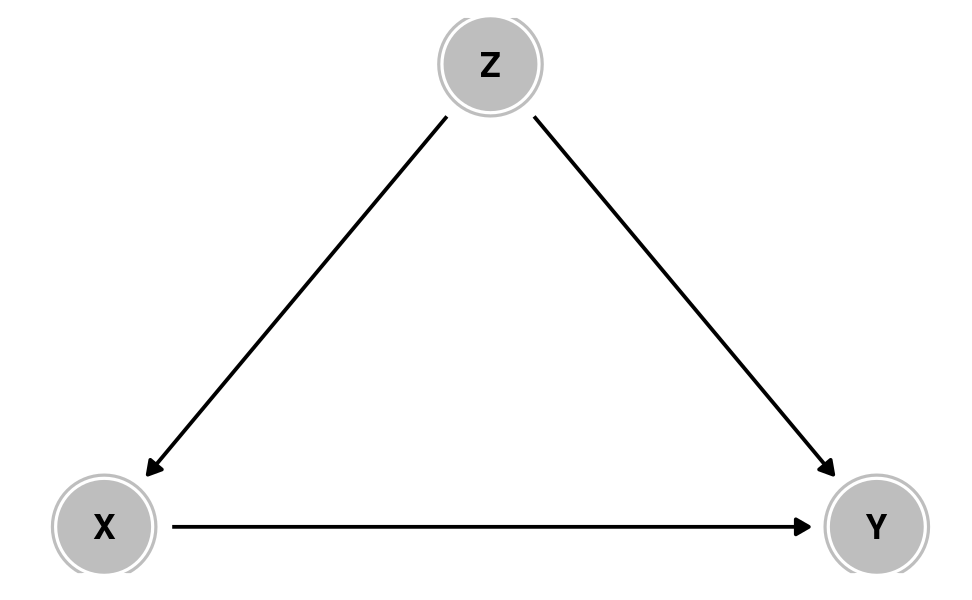

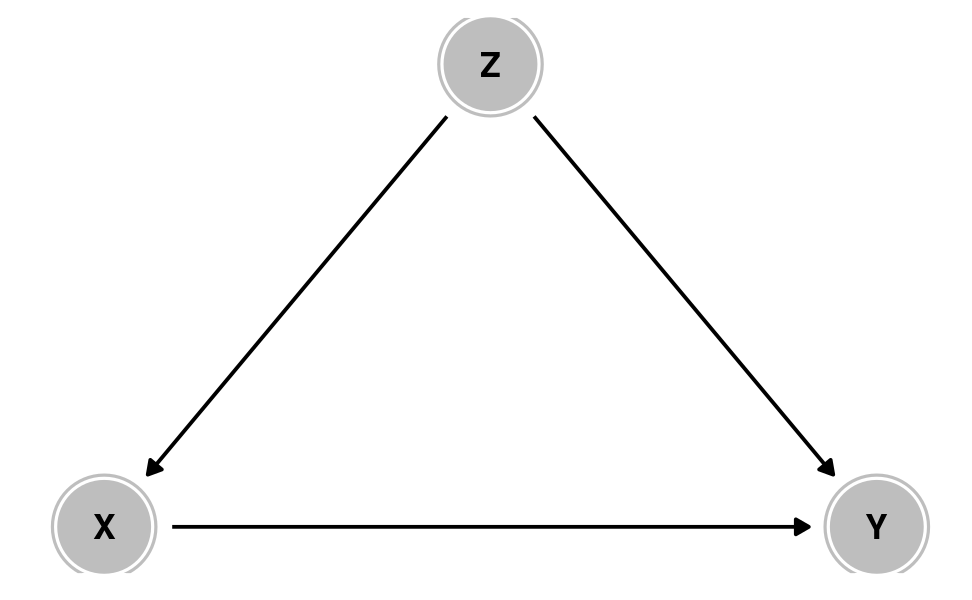

Confounding

Common cause

Causation

Mediation

Collision

Selection /

endogeneity

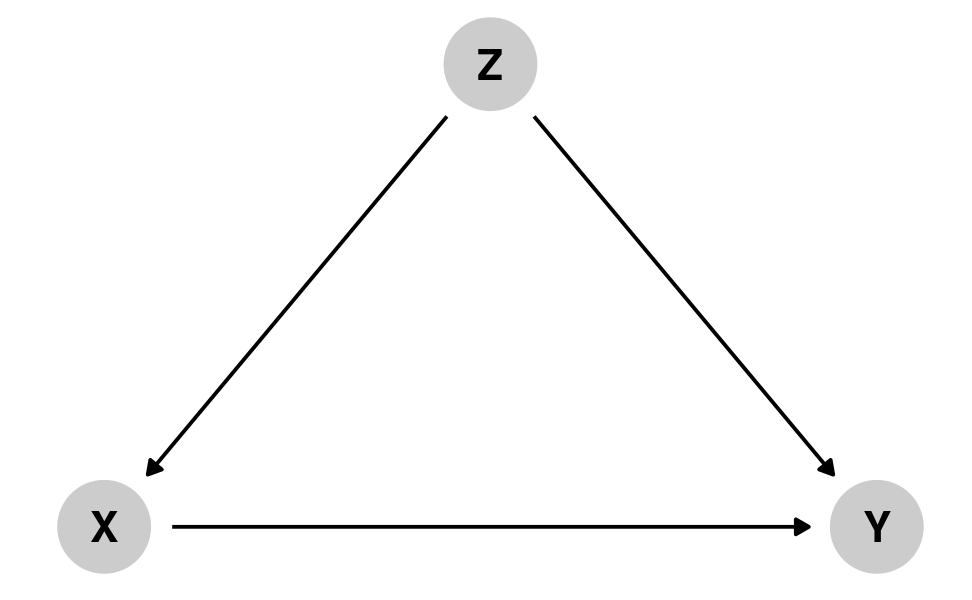

Confounding

X causes Y

But Z causes both X and Y

Z confounds the X → Y association

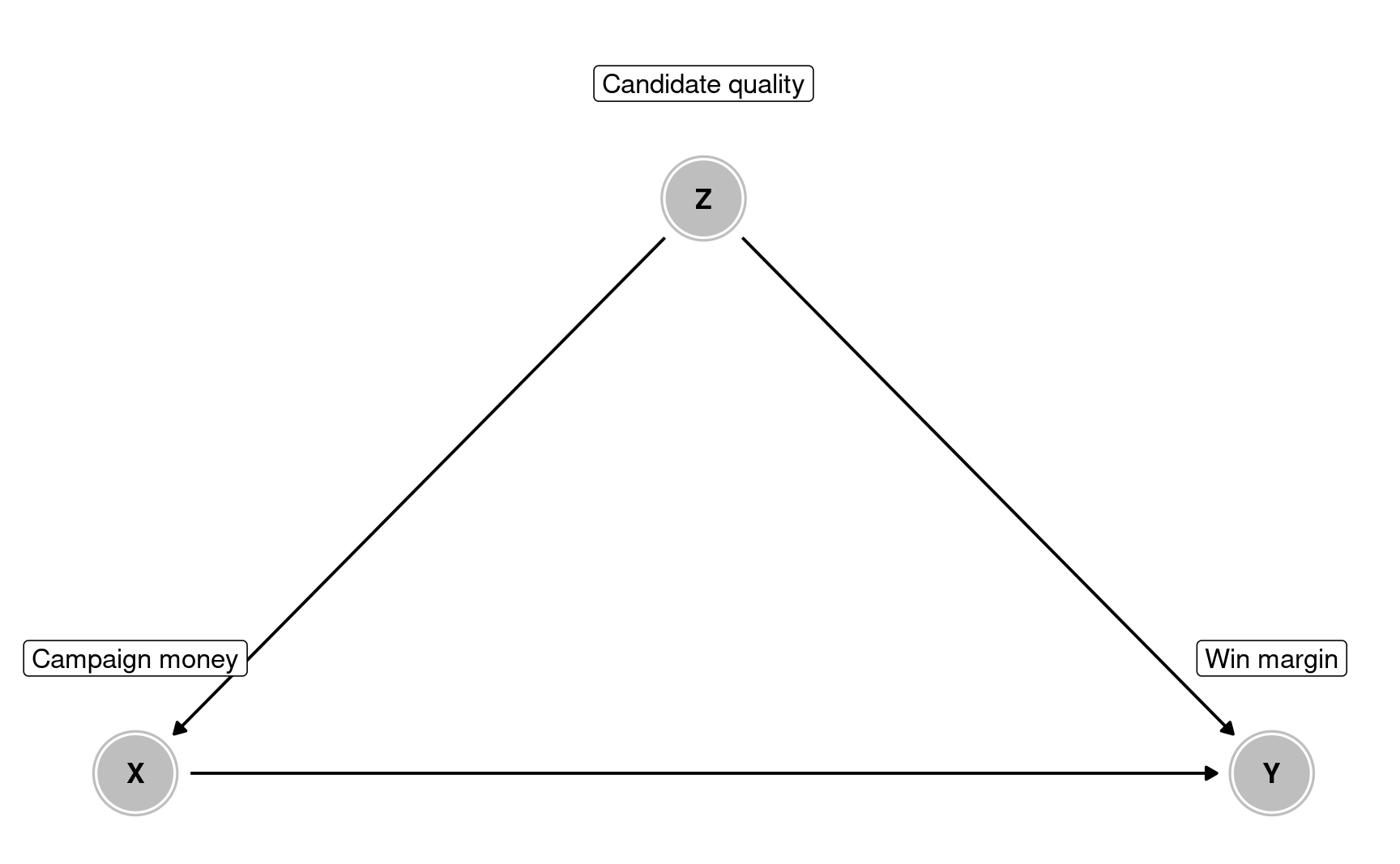

Confounder: effect of money on elections

What are the paths

between money and win margin?

Money → Margin

Money ← Quality → Margin

Quality is a confounder

Experimental data

Since we randomize assignment to treatment X, all arrows incoming in X are removed.

With observational data, we need to explicitly model the relationship and strip out the effect of X on Y.

How to adjust with observational data

- Include covariate in regression

- Matching: pair observations that are more alike in each group, and compute difference between these

- Stratification: estimate effects separately for subpopulation (e.g., young and old, if age is a confounder)

- Inverse probability weighting: estimate probability of self-selection in treatment group, and reweight outcome.

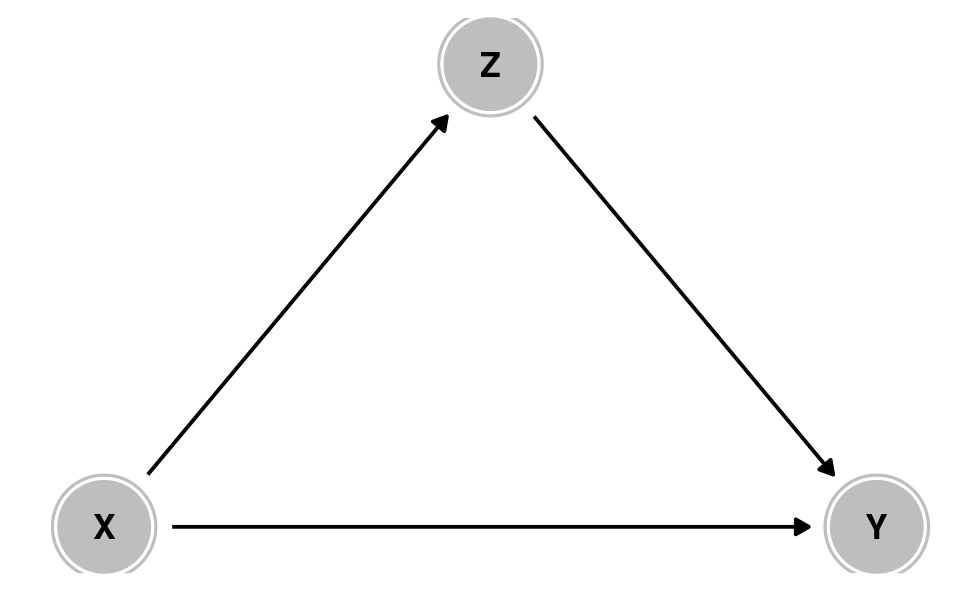

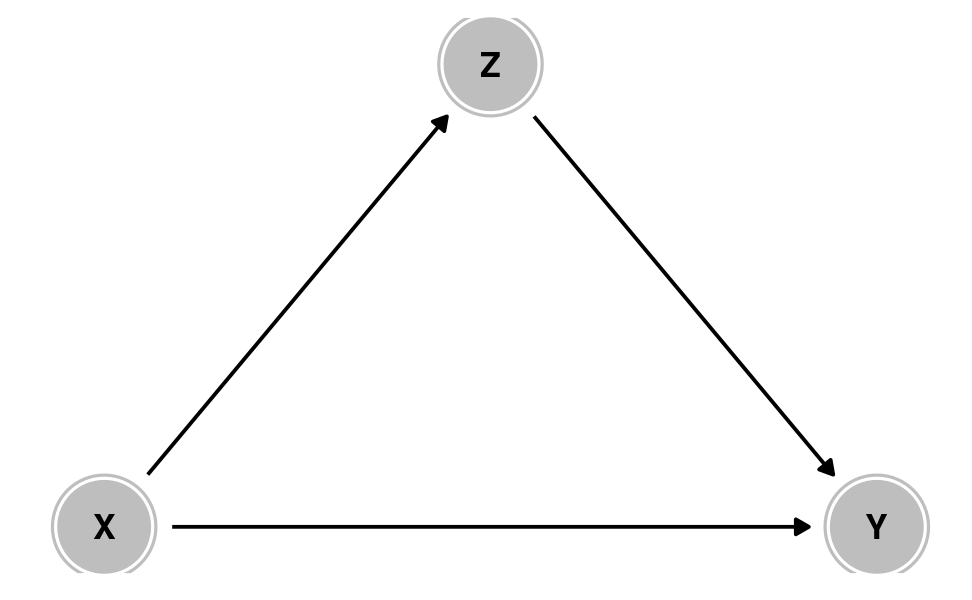

Causation

X causes Y

X causes

Z which causes Y

Z is a mediator

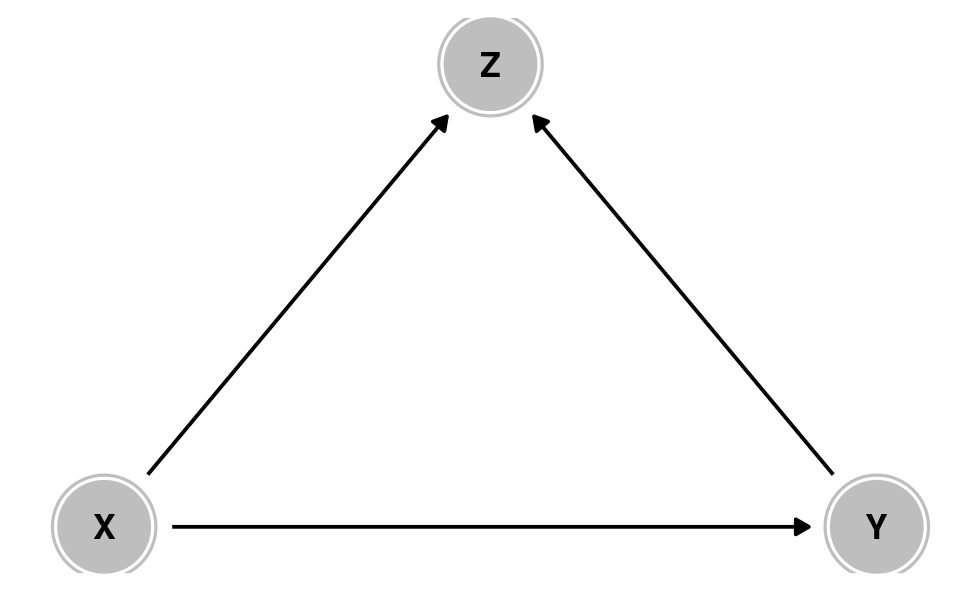

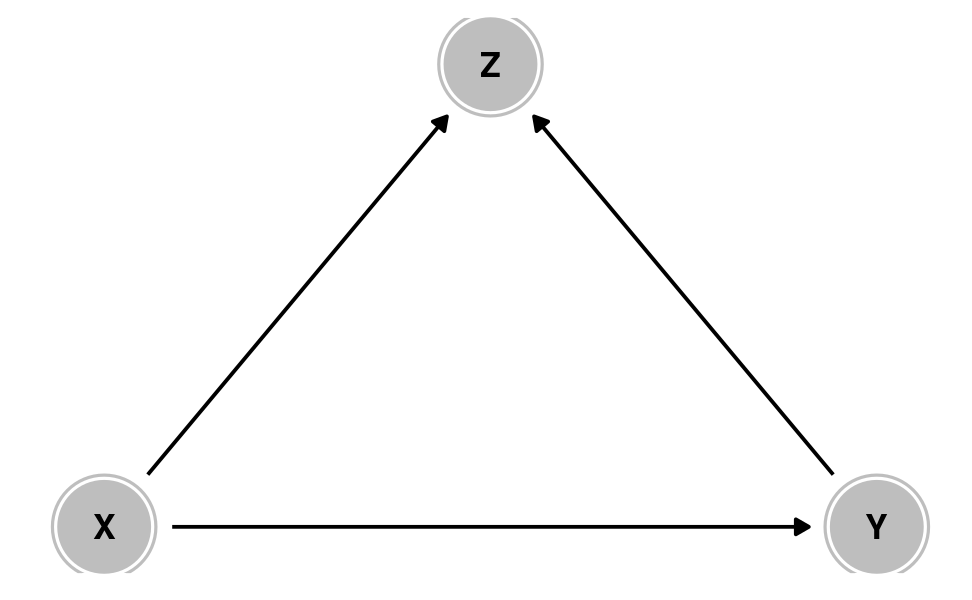

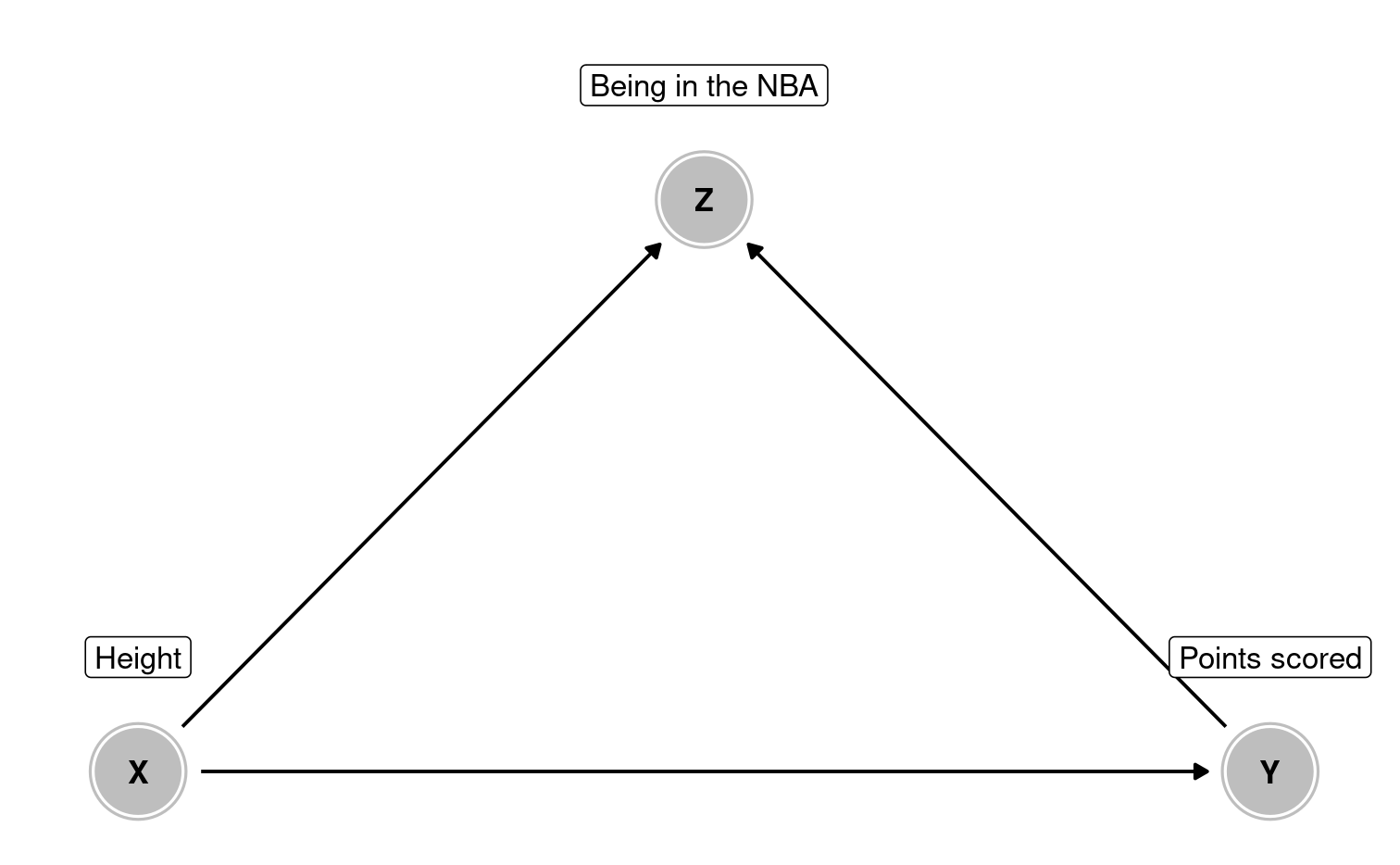

Colliders

X causes Z

Y causes Z

Should you control for Z?

Colliders can create

fake causal effects

Colliders can hide

real causal effects

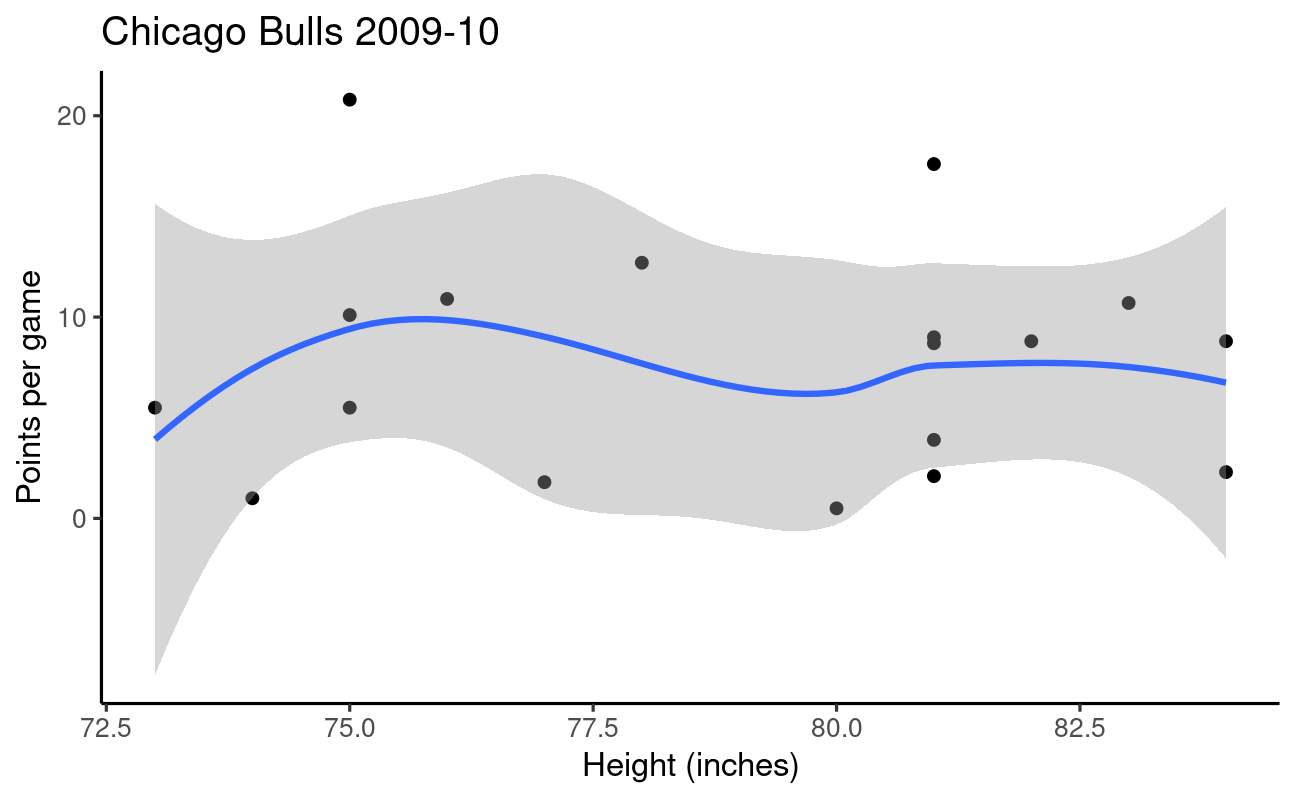

Height is unrelated to basketball skill… among NBA players

Colliders and selection bias

A new collider bias teaching example. Sample selects on marriage (not divorced) so: satisfaction ––> [not divorced] <–– children (Richard McElreath, Apr 26, 2021 on Twitter)

Example of confounder: https://doi.org/10.1177/109467051454314

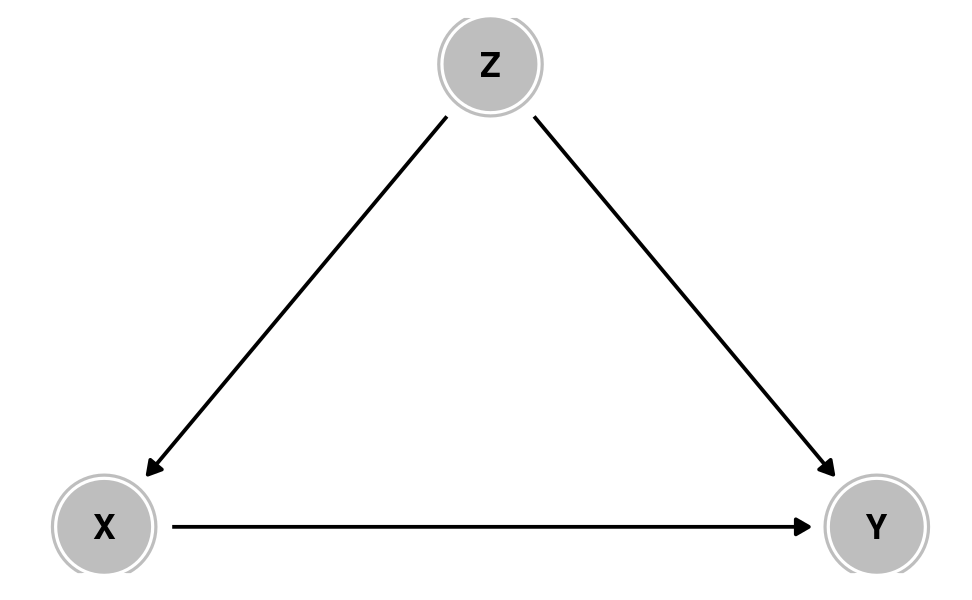

Three types of associations

Confounding

Common cause

Causal forks X ← Z → Y

Common cause

Causal forks X ← Z → Y

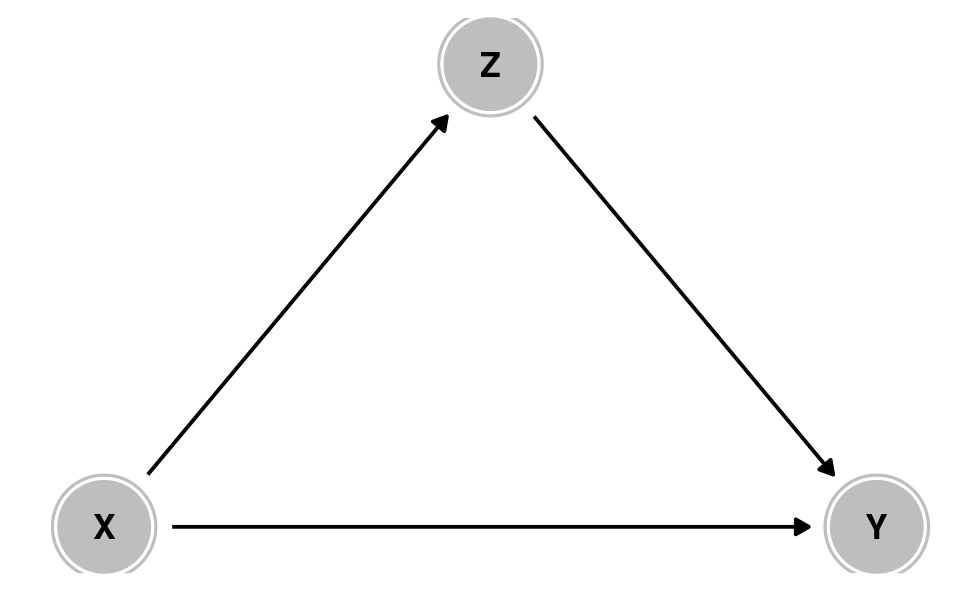

Causation

Mediation

Causal chain X → Z → Y

Mediation

Causal chain X → Z → Y

Collision

Selection /

Selection /

endogeneity

inverted fork X → Z ← Y

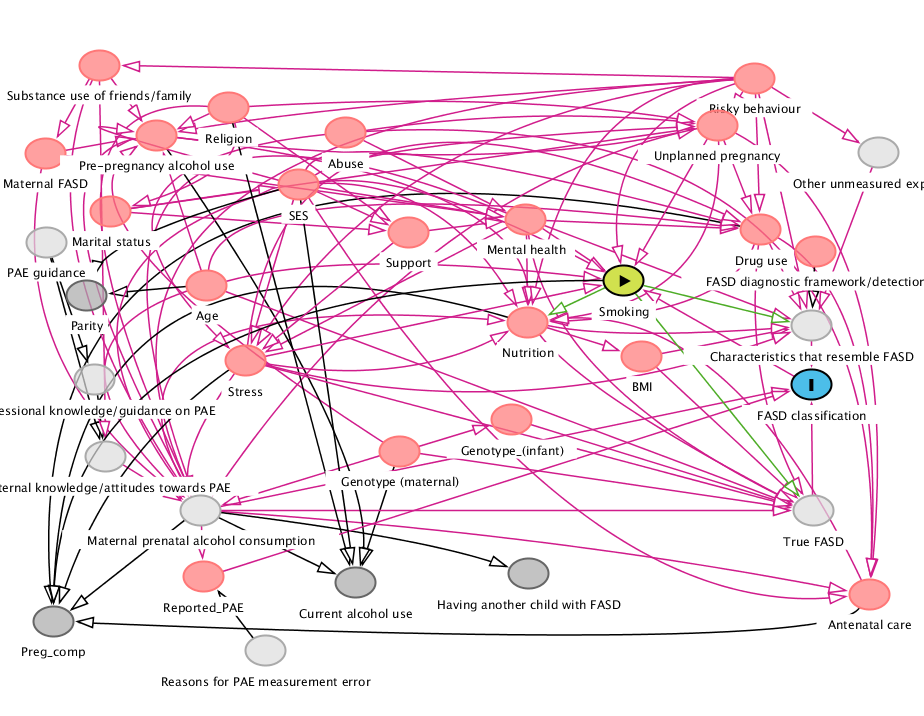

Life is inherently complex

Postulated DAG for the effect of smoking on fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD)

Source: Andrew Heiss (?), likely from

McQuire, C., Daniel, R., Hurt, L. et al. The causal web of foetal alcohol spectrum disorders: a review and causal diagram. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 29, 575–594 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1264-3